The purpose of this program is to recognize AKC dogs and their owners who have given their time and helped people by volunteering as a therapy dog and owner team.AKC Therapy Dog™ program awards an official AKC title awarded to dogs who have worked to improve the lives of the people they have visited.

The AKC Therapy Dog title (THD) can be earned by dogs who have been certified by AKC recognized therapy dog organizations and have performed 50 or more community visits.

AKC does not certify therapy dogs; the certification and training is done by qualified therapy dog organizations. The certification organizations are the experts in this area and their efforts should be acknowledged and appreciated.

Why Did AKC Start A Therapy Dog Title?

AKC has received frequent, ongoing requests from dog owners who participate in therapy work to "acknowledge the great work our dogs are doing." Many of our constituents are understandably proud of their dogs.

Earning an AKC Therapy Dog title builds on the skills taught in the AKC S.T.A.R. Puppy® and Canine Good Citizen® programs which creates a sound and friendly temperament needed by a successful therapy dog.

A SAMPLE THERAPY DOG CERTIFICATION TEST

Phase I

The dog must wear either a flat buckle or snap-in collar (non corrective) or a harness (non-corrective). All testing must be on a 6 ft. leash.*

*If the dog is on a longer leash, a knot must be made in the leash to mark 6 ft. The handler must drop the excessive leash.

Entry Table (Simulated as a Hospital Reception Desk)

Test #1: The dog/handler teams are lined up to be checked in (simulating a visit).

The evaluator ("volunteer coordinator") will go down the line of registrants and greet each new arrival including each dog. At the same time the collars must be checked, as well as nails, ears and grooming.

This is to simulate the arrival at a facility where the coordinator first greets the visiting dog team and instructs the handler on proper grooming before a therapy dog visit.

The dogs must permit the evaluator to check the collar, all 4 paws, ears and tail which must be lifted if applicable

The dog must be friendly and outgoing upon meeting the evaluator, willing to visit without being invasive and show impeccable manners.

Pulling, lunging, jumping up (unruliness), shyness, aggressiveness, or resisting examination is an automatic failure.

Check-in and out of sight (between 2-3 minutes)

Test #2: The handler is asked to complete the paperwork and check in. At that time a helper will ask the handler if he/she can help by holding the dog. If the handler prefers he/she can go with the helper and places the dog with a stay command. The dog will be out of sight of the handler. Another helper will take charge of the dog. The helper can talk to and pet the dog. The dog can sit, lie down, stand or walk around within the confine of the leash.

Whining, barking, pulling away from the helper is an automatic failure.

Getting around people

Test #3: As the dog/handler team walks toward the patients' rooms, there should be various people standing around. Some of the people will try visiting with the dog. The dog/handler team must demonstrate that the dog can withstand the approach of several people at the same time and is willing to visit and to walk around a group of people.

Walking around and through a group of people should be done randomly.

Pulling on the leash, jumping up, shyness, not wanting to visit, showing aggressiveness, not walking on a loose leash are an automatic failure.

Group sit/stay

Test #4: The evaluator will ask all the participants to line up with their dogs in a heel position (w/dog on left), with 8 ft. between each team. Now the handlers will put their dogs in a sit/stay position. The Evaluator will tell the handlers to leave their dogs. Handlers step out to the end of their 6 ft. leash and wait for the evaluator’s command to return to their dogs.

Group down/stay

Test #5: Same as test number 4, except dogs will now be in a down/stay.

The dogs must stay in place as ordered.

These exercises will show how well the dog responds when other dogs are present.

Not staying in place, trying to visit with another dog are reasons for automatic failure.

Recall on a 20 ft. leash

Test #6: All handlers will be seated. Three dogs at a time will be fitted with a long line. One handler at a time will take the dog to a designated area and downs the dog. Upon the command from the evaluator the handler will tell the dog to stay. The handler will walk to the end of the 20 ft. line, turn around and upon a command from the evaluator will recall the dog.

For all practical purposes the recall is one of the most important obedience exercises for the dog to master. If a dog does not come when called the dog is not obedient and cannot be trusted in public.

Not staying in place and coming when called is reason for automatic failure.

Visiting with a patient

Test #7: The dog should show willingness to visit a person and demonstrate that it can be made readily accessible for petting (i.e. small dogs can be placed on a person's lap or can be held; medium and larger dogs can sit on a chair or stand close to the patient to be easily reached).

For this part of the test a wheelchair or bed can be used. The evaluator will supply a rubber bathmat and a towel.

Shyness, aggressiveness, jumping up, not wanting to visit are reasons for automatic failure.

Phase II

Testing of reactions to unusual situations

Test #8: The dog handler team must be walking in a straight line. The dog can be on either side, or slightly behind the handler, the leash must not be tight. The evaluator will ask the handler to have the dog sit (the handler may say sit). Next the evaluator will ask the handler to down the dog. Continuing in a straight line, the handler will be asked to make a right, left and an about turn at the evaluator's discretion.

The following distractions will be added to the heel on a loose leash.

a. The team will be passing a person on crutches.

The dog must visit with the person on crutches.

b. Someone running by calling "excuse me, excuse me" waving hands (this person is running up from behind the dog. It could also be a person on a bicycle or on roller blades).

The dog cannot be startled, can be curious, but not aggressive or shy.

c. Another person should be walking by and drop something making a loud startling noise (a tin can filled with pebbles, or a clipboard). At an indoor test one could use a running vacuum cleaner (realistic in a facility).

The dog cannot be startled, it can be curious, but not aggressive or shy.

d. After that, the team should be requested to make a left turn.

To make it more realistic the left turn should be around some people.

The people should be shuffling, moaning, coughing and also talking loudly.

Various health care devices should be used by the people (wheelchairs, crutches, (etc.)

e. And a right turn.

To make it more realistic the right turn should be around some people.

Same scenario as (d)

f. After the right turn an about-turn, going back in a straight line.

Exercises "a - f" show us how a dog will react under various circumstances which are day to day occurrences when the dog is out in public or while visiting at a facility.

The following scenarios can be staged as such:

As the dog handler team walks in a straight line, a person in a wheelchair, with a walker or crutches should be encountered by the dog handler team. Each time the dog is required to visit.

These exercises give the Evaluator a good opportunity to observe the dog in various situations. Do not pass the dog if the dog does not behave well in public.

Leave it; phase one

Test #9: The dog handler/team meets a person using a walker, the dog should approach the person and visit. The person with the walker will offer the dog a treat.

The handler must instruct the dog to leave it.

The dog must ignore the food. The handler should explain to the patient why the dog cannot eat a treat while visiting (i.e. dog has food allergies).

Leave it; phase two

Test #10: The dog handler will resume walking in a straight line with the dog at heel. There will be a piece of food in the path of the dog. The dog must leave it.

If the handler spots the food, a command of leave it can be given and the dog is not permitted to pick up the food. If the handler does not see the food and consequently does not give a command, he/she is not scouting adequately. Regardless the dog is not permitted to pick up the food.

The Leave it exercise is a very important part of the test. A dog who is food oriented will pick up food from the floor, the food might be potentially harmful to the dog (pills etc.) Having a patient feed a dog can also cause a potential problem. Some dogs are very grabby and might injure the patient.

Meeting another dog

Test #11: A volunteer with a demo dog will walk past the dog handler/team, turn around and ask the handler a question. After a brief conversation, the two handlers part.

The dog should not show any kind of negative reaction. The handler should not allow the dog to visit with the demo dog.

Entering through a door to visit at the facility

Test #12: The dog handler team is ready to enter a door to the facility. The handler first has to put the dog in a sit, stand or down stay, whichever is appropriate for the dog. If there is no door available, an area simulating an entrance should be marked. A person should be able to go through the entrance before the dog/handler team.

This test will show us that the handler has control over the dog reinforcing that a responsible handler will yield to others.

Reaction to Children

Test #13 must be given last and only if the dog/handler team has passed all other segments of the test.

Test #13: The last phase of the test shows us if the dog will be able to work well around children.

The dog's behavior around children must be evaluated during testing. It is important that during the testing the potential Therapy Dog and the children are not in direct contact. This means the dog can only be observed for a reaction toward children running, or being present at the testing site. The evaluator must designate an area at least 10 feet away from the dog and handler. The dog may be walked, or put in a sit or down position. The children will be instructed to run and yell and do what children usually do while playing.

Any negative reaction by the dog will result in automatic failure. Negative reaction means a dog showing signs of disobedience, aggression or avoidance (shyness).

TEAMWORK

Therapy Dogs are dogs who go with their owners to volunteer in settings such as schools, hospitals and nursing homes.

From working with a child who is learning to read or providing encouragement to the sick or injured, to visiting a senior in assisted living, therapy dogs and their owners work together as a team to improve the lives of other people.

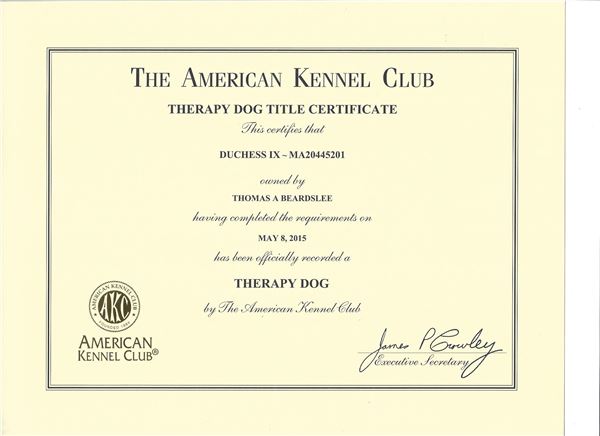

Therapy Dog Duchess and Friend at the 2013 Red Cross Christmas Party

Have Questions?

If you are in need of a Therapy Dog to provide comfort to someone, please feel free to contact us at 573-450-3221 to arrange a visit. We welcome your questions and queries. Please see our Contact Us page for complete contact information.